Jamex and Einar de la Torre

May 4 - June 16, 2001

Yes is not the typical response to an either/or question, but Einar and Jamex de la Torre prefer not to exclude possibilities if they can help it. Inclusion, especially with all of its messiness and contradictions, is by far their more natural mode and a more pertinent prism through which to consider their work: Is it glass art, installation, painting, or sculpture? Yes. Are Einar and Jamex Mexican or American? Yes. Are they social critics, historians, pop artists, or conceptualists? Yes. Is their work sensationalistic or is it wise? Yes.

Though the de la Torres' work doesn't literally move (with a few exceptions), neither does it stay still. It pulses with contradiction and irreverence, it careens between different cultural references, veers among different time periods, jerks from humor to condemnation to lament. It defies allegiance to any single medium or subject or timeframe. It resists the conquest inherent in definition.

Conquest is the operative term here conquest as the paradigm that plays itself out all too often when unlike entities meet, whether cultures, races or sexes. One defines and dominates the other, devouring it, dehumanizing the victims and strutting away with a victor's self-satisfaction. In a new diorama by the de la Torres, the Spanish conquistador par excellence, Hernán Cortés, storms on the scene of 16th century Mesoamerica, looking and acting like Godzilla, with the help of an extra set of arms like a Hindu god, Einar and Jamex say, or an insect. With fury and contempt for the pagans underfoot, the rampaging Cortés kicks an Aztec pyramid built of glass, his eyes gleaming like lasers.

White skins subjugating brown and black skins; Catholicism subsuming the faiths of the Mayans, the Toltecs, the Aztecs; men dominating women in classic patriarchal fashion in the de la Torres' work, conquest is conquest, wherever it occurs on the continuum. Insidious, less visible forms of subjugation like stereotyping and ethnic self-hate feed the larger beast too, and whatever poetry the intersecting cultures could have written together devolves instead into a tragedy told in terms of contamination, distortion and desacralization.

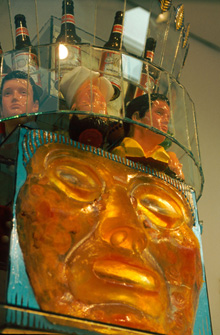

From a map of Mexico formed of blown glass intestines, to a wall of icons looking like gaping glass vulva, the de la Torres' work churns with the promises and curses of vexed unions (political, religious, racial, sexual...). Its extravaganza of forms and textures invites a response in kind - baroque, lavish, intense, multilayered and irreducible. Laughter is usually what comes first, and easiest, because some of the work is truly funny. Outrageous in its combinations and juxtapositions, outlandish in its mix of materials, it never ceases to be brash and surprising.

But laughter can also signal unease. It enters the dialogue like an audible punctuation mark, an ellipsis...encouraging a pause (where the difficult stuff gets sorted, edited out) and a shift to another, less challenging subject. Laughter of this sort masks fear, confusion, perhaps also the exhaustion induced by such visual excess. It feels hard, at times, to get traction on the work. And in spite of, or perhaps because of its merciless sensuality, the de la Torres' work can also feel threatening. It insists on destabilizing comfortable categories of knowledge and established hierarchies. It disregards taboos (American, more than Mexican) keeping sex, death and religion from touching on the plate.

The space where they do touch, and overlap, their juices mixing in an intriguing, piquant puddle, is where Einar and Jamex de la Torre settle in and do their work. On that very fault zone, where Mexico meets the U.S., craft meets art, pop culture meets high concept, past meets present, the beautiful meets the grotesque, the sacred faces off against the profane. Their work is not just bicultural - like them born in Mexico, raised primarily in the U.S., and living and working in both countries but polycultural - a luscious braid of multiple constituent strands. Their guiding impulse is inclusiveness. The freedom of their vision is liberating. Nothing is exempt from their grasp. Their works are artifacts of a realm without limits, hybridized, cross-fertilized, spiked with discord and potential. Do these mementos hark from the utopian future or the dystopian present? Are they promises, threats, or realities? Yes. Yes.

We prefer ambiguity to moralizing. We just put the images out there. We're not interested in the work as an end that we've figured out, a statement that's done, and you either get it or don't get it. We're a lot more interested in making a stacking of images, like the layering of an onion. We're definitely not interested in conclusions.

In a new work for Grand Arts, the de la Torres have constructed two large ferris-type wheels that turn at different speeds. They suggest the friction of anachronism, of two time zones and sensibilities out of sync with one another, yet they could also be updated versions of the Mayan calendar, also a two-wheel affair, with solar and sacred calendars intermeshing like cog wheels, one turning inside the other. Another derivation for the work could be the Aztec calendar stone, a replica of which served as a coffee table in the de la Torres’ family home. The original 12-foot-diameter disc features the face of the sun god Tonatiuh at its center, and to either side, large claws grasping human hearts. Human blood is what nourished the gods of the Aztec cosmogony, keeping the sun victorious over the forces of night. As one of the de la Torres' wheels turns, hearts dip into a canoe and emerge wet, dripping red. Every culture, and certainly every collision of cultures, entails sacrifice. What, the artists prompt us to consider, do we give up to keep our wheel turning, to appease our 21st century gods?

For another pair of new sculptures, Einar and Jamex de la Torre looked to monumental Toltec guardian figures for inspiration. Their seven-foot-tall Tula boys (named after the principle city of the Toltecs) are built of clear glass compartments that function like transparent skins, exposing found objects within, emblematic of guts, bones, motivations. In one of them, an upright shotgun doubles as legbone, and golf clubs serve as feet, each club-head a toe. One Tula boy symbolizes an American warrior and the other a Mexican. Both cultures, the de la Torres agree, nurture a strong machismo mentality.

Several glass, skull-like heads made by the artists in recent years have the popping eyes of Tezcatlipoca, the Mesoamerican god who wielded a smoking mirror that enhanced his powers to foretell the future and peer into the hearts of men. A new series of painted cut-outs adapted from Mayan glyphs reads like a sprightly decorative frieze, but nothing the de la Torres do is as neutral and naive as wallpaper. These, too, push a limit, branding the sacred Mayan symbols with corporate logos and equipping the animal figures with cell phones. The de la Torres dip readily into the rich visual and conceptual pool of Mesoamerican culture, a world as saturated with transmutations as anything they could have dreamed up themselves. Are the references to pre-Conquest Mexico simply there as gifts from the past, to enrich the present? As reminders of what the Spanish snuffed out? Or are they meant more aggressively, to jolt us into recognizing how vacuous the belief systems driving our own culture are, compared to those of our predecessors? Yes, yes, yes.

History cannot be broached objectively. We can't help but see the age of stone carving through the eyes of the plastic, throwaway present. No sense trying for neutral clarity.

It's an impossibility. There's always a bent, there's always an angle or a core constituency that gets addressed, and therefore [the telling of history] is ripe for misinformation.

Better, then, to broadcast those received myths as exactly that, as misinformation, and expose it, distend it, caricature, lampoon and skewer it. The de la Torres, themselves, have been subject to snowballing misperceptions: that they are 'glass artists', that working in glass constitutes a craft, and that craft is secondary to art.

In the glass world, in all of the craft world, everyone wants to be called an artist. We certainly love glass, but if we didn't do glass, we'd be doing something else. We're just fluent enough in it to be spontaneous, but we're careful that we're using it for the right reasons. The way we describe it is, is the medium working for you, or are you working for the medium?

Einar and Jamex de la Torre learned the technique of blowing glass at California State University, Long Beach in the early 1980s, and have been using it voraciously ever since, in their individual work and in the work they've made collaboratively since the early 1990s. Glass turns up in the de la Torres' work as flame, as liquid and as flesh. It's an especially appropriate medium for them because of its fluidity, its ability, being both strong and fragile, to reconcile opposites. While their use of glass is certainly distinctive, their inclusionary take on the material world renders it one texture, one surface among many. Fake fur, wooden crosses, old photographs, dice, beer bottles, satellite dishes, video screens, syringes, tools, toys, and trinkets spill from the grand junk drawer of our time into their sculptures, each item preloaded with cultural baggage and contextual associations that then get skewed and reconfigured.

Their accretive process of image-building is common to assemblage practice, but also to the making of shrines and altars studded with offerings. Each image has found its way into the mix by virtue of being a symbol or attribute of power religious, commercial, political or personal. From the feathered serpent Quetzlcoatl to the Nike logo, every element bears a measure of value, assigned by its originating culture according to its capacity to sustain a specific aspect of life. By unabashedly leveling the playing field, so that ancient gods fuse with corporate logos, and objects of worship consort with objects of superficial pleasure, the de la Torres make you stop, laugh, and wonder: Is nothing sacred? Or is everything sacred? Yes, absolutely, yes.

Leah Ollman

12 April 2001

San Diego, CA

Back to top

|

|