Larry Buechel

Eye to Eye

April 21 - June 23, 2000

The key symbol in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby is a

decrepit advertisement for the optometric services of Dr. T. J.

Eckleberg. The faded billboard illustrates a pair of eyes, "blue and

gigantic - their retinas are one yard high," framed by yellow

spectacles. The eyes gaze across a "valley of ashes" (the Corona

dump in Queens) that the novel's characters pass through several

times in their travels between Long Island and New York City. After

his philandering wife is killed in a car accident, the owner of a gas

station adjacent to the "valley of ashes" speaks to his neighbor while

staring out the garage's rear window.

" - and I said, 'God knows what you've been doing, everything you've been doing. You may fool me but you can't fool God!'" The neighbor, shocked to see that the widower is staring at the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleberg, attempts to offer reassurance. "That's an advertisement," he says.

The gamut of metaphoric possibilities Fitzgerald offers up in this

single, loaded image is fully exploited by the sculptures that

comprise Larry Buechel's exhibition Eye to Eye. From the profound

concept of the "eye of God" to mascara marketers' effortless

co-option of the parliamentary proclamation, "The ayes have it,"

Buechel's sculptures reflect the range of ocular iconography that

permeates human history.

The ancient Egyptian utchat, symbol of the eye, was painted on

coffins and sarcophagi to ward off evil, and the Egyptian custom of

painting eyes on boat prows to guide sailors through storms remains

widespread on the Mediterranean today. A picture of an open hand

with an eye in the palm, found in both Oriental and Native American

imagery, is seen as a symbol of mercy, signifying the marriage of

awareness and acceptance. An early ideogram for air a circle with

a dot in the center resembles the eye and so links the

ever-presence of air with the ever presence of an all-seeing

awareness.

God is described as omnipresent (all-present), omnipotent (all-powerful), and omniscient (all-knowing). Here the "knowing" is

understood to mean "seeing," just as the caution to children that Santa "knows when you are sleeping/he knows when you're

awake," is taken to mean that he sees into the children's homes.

This sampling of eye-related references suggests that human awareness has always accommodated the concept of

surveillance, and, further, that most moral structures are grounded in the concept of surveillance. (In art this is reflected,

however accidentally, in the "following-eye" or "Mona Lisa" effect, wherein the front-focused stare of the painted figure seems

to pursue a viewer around the room.) Yet it is only recently that this watchful presence has transmuted from a metaphoric

entity to a literal one: the electronic eye scanning bar codes, the video camera recording ATM transactions, the satellite

monitoring weather patterns and weapons build-ups.

In the mid-1940s, Italian sculptor Lucio Fontana foresaw technology's potential to drastically alter human beings' innate,

multisensory response to the environment and to one another. "Sensation was everything with the primitive man; sensation in

the face of misunderstood nature, musical sensations, rhythmic sensations." Fontana also predicted that artists would

neither keep pace with nor deter the onrush of commercial technological dynamism, although he held out hope that kinetic art

might somehow help re-engender the "original condition of man."

Fontana was at least half-right: In a world increasingly dominated by computer-generated imagery, the usefulness of taste,

touch, smell, and hearing has steadily ebbed while the significance of vision has expanded exponentially. New York-based

ceramist Marek Cecula speaks fervently of the need to protect his own area of expertise, that of tactile experience, from

extinction. "We can lose the sense of touch. It's getting numb through too much exposure to the purely visual."

Buechel came of age as an artist in the 1980s,

when the concept of "sculpture" had been blown

wide open and there were no longer any

restrictions as to form, media, or content. His

astuteness about when and where to incorporate

commercial products and/or manufacturing

techniques, along with his own faultless

craftsmanship, allows the individual sculptures to

present themselves as seamless, high-tech

"totems" (rather than fussed-over objects), each

work declaring via its media and organization the

"state of the art" of a particular aspect of

21st-Century visualization.

Palace Guard is an industrial doormat (the ultimate

symbol of that which is taken for granted),

custom-woven with the image of a single,

unblinking eye. Like the proto-bionic protectors of

Buckingham Palace, the anonymous,

machine-made mat implacably registers the

comings and goings of gallery visitors.

At the opposite end of the technological

spectrum, Eye Contact is a ten- by

fifteen-foot computer-generated digitized

painting of the artist's right eye, hugely

enlarged from a 4x5 photo and precise

enough to allow an iridologist to assess

the artist's health.

Hello is a remote-controlled electronic

transit mounted on a surveyor's tripod.

The robot-like unit's "face" is covered by

a transparent photo of the artist's eye.

When the sculpture/robot is in its

dormant phase, the transit tips down.

When activated by the approach of a

gallery visitor, the transit tips up and

rotates in the visitor's direction. Buechel

has opted to limit the machine's range of

functions to the simplest and most

essential component of good manners.

"It sleeps, with its head down, until

someone comes near. Then it wakes up

and acknowledges the presence."

Encore is a series of identical elements,

arranged in tiers to accommodate viewers'

various heights. A light-gathering pin from an

archer's bow-sight produces a luminous

red-orange dot, like the focus point projected

from the laser scope of a high-powered rifle, in

front of the pupil of a glass eye (a genuine

prosthesis from the 1940s). Each eyeball and

light-point are magnified behind a convex

tank-sight lens. The sculpture's title suggests a

Kafkaesque drama in which the array of

pseudo-optical instruments serves as an

audience or jury, each member armed only with

vision ("seeing is believing"), but to a degree of

accuracy achievable only with

electromechanics. The viewer, caught in the

sculpture's crosshairs, is under serious scrutiny.

Buechel relates Observatory to the attempts of

immigration officials to maintain constant

vigilance along US borders. Four video monitors,

each projecting the image of a blinking (and

therefore alive and attentive) eye, spin on a

motor-driven turntable, creating the illusion of a

360-degree band of unbroken surveillance.

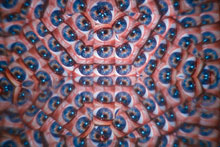

With the mechanics of Kaleidoscope hidden from view, only the sculpture's

final effect is available to viewers. The video-projected blinking-eye image is

multiplied many times over by a series of Fresnel lenses (highly efficient

concentric-ringed optics used in cameras and lighthouse beacons) and then

further fragmented through a five-foot prism.

When Fontana predicted that kinetic art was a means to engage all the

senses, he was referring to art in the modernist sense that is, art as a

self-contained object, created to be viewed within an aesthetic context. The

kinetic component, it was hoped, would help to "engage" the viewer. This

aim was elaborated upon by French sculptor Julio Le Parc in a 1962 essay:

"To cause the active participation of an art work is perhaps more important

than passing contemplation and can develop the natural creative instincts

within the public."

That was the modern then. This is the postmodern now. Buechel's

sculptures speak to Western culture at large, not just to its art-world

component, and they aim far beyond the science-fair goal of stimulating

viewers' "natural creative instincts." Like the ad for Dr. T. J. Eckleberg, they

function less as objects than as commentary, layered with hard information

about a profound development in human evolution. And though laced with a

touch of humor (also like Fitzgerald's billboard), these works project no

judgment. It's up to us to decide what we think about all this seeing and

being seen.

Roberta Lord

March 2000

New York, NY

Back to top

|

|