|

|

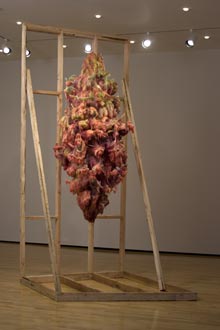

| Neal Rock Faith Culture Collection March 24 - June 3, 2006 Rock of the Age It's perhaps treacherous to make a comparison between Jackson Pollock and a contemporary artist, but Neal Rock leaves one little choice. Such comparison is not about men or myths, but rather the qualities and aspects, as well as perceptions, of works and practices. Neal Rock's works, in which substrates are engulfed in pigment-infused silicon squeezed from improvised tools akin to a chef's icing bag, are pieces of art that simultaneously insist, radically so, on announcing and exploring their own literal presence, and on exploring the evocative potential of such presence outside of traditionally understood categories of abstraction or representation, and this is where they relate to and depart from the work of Pollock. Rock's works lie, as has already been noted multiple times in his young career, somewhere between painting and sculpture. Such an observation is perhaps obvious, and certainly could be made about work by many artists, but it is key to understanding how Rock falls within a literalist understanding of painting, and a lineage of painting born of such understanding. His works are the descendents of paintings by the likes of Janet Sobel, a little known self-taught artist who in the 1940s began making work by, in addition to pouring and dripping, also puddling liquid paint on a surface and then tilting the surface and blowing on the paint through a straw in order to get it to run in various directions. The results are perfect examples of what would come to be known as all-over painting-works in which an accumulation of material deposits made via the artist's gesture yields an active yet even field laced through with subtle variations and punctuations. Such a description perhaps more familiarly connects with the all-over paintings of Pollock, who was influenced by Sobel, and whose works are the best known early antecedents of Rock’s works, which indeed radicalize the concept of all-over painting-piling up, getting all over itself, and more recently, getting all over the place. And though the works are in fact wholly solidified, the silicon looks so forever gooey as to leave you with the uneasy feeling that with one false move, it might be all over you. Many of Pollock's paintings suggest the beginning of a trajectory of what was to become known as action painting and/or process-based painting, which Rock's works take to a kind of extreme logical end. But it is Pollock's painting No. 29, 1950, a painting made on a sheet of glass, that most clearly relates. Unlike his other canvases, in which the compositions ultimately resolve themselves at the imposing boundaries of the rectangular stretcher bars, No. 29 resolves itself as a shape established by the web of paint and other materials as the glass fades from view. The substrate disappears; the logic of painting as pure paint is taken to its own extreme end. Rock's works, which envelop their substrates, also ultimately establish their forms via the paint-like material itself, but pushing much further into three dimensions. Rock's works continue with some of the business Pollock left unfinished with No. 29, a work that also is significant in that it is the painting Pollock made while being filmed from underneath the glass by Hans Namuth, whose film and still photographs confirmed what already was evident in the work of Pollock and other mid-century gestural painters-that the inevitable extension of formalist and expressionist understandings of paintings was a new literalism. The formalist fascination with raw material (paint) on surface, and the expressionist-oriented preoccupation with the mark as record of creative act, gives way to a heavy emphasis on the work of art as a literal arrangement or organization of material. Pollock and Namuth helped to secure this emphasis in filming the artist depositing not just paint, but string, pebbles, bits of glass, and scraps of expanded steel mesh on the glass. These things, which we know as varieties of stuff, reinforced the materiality of the paint, which becomes less the medium with which one makes figurative pictures or abstract compositions, but just stuff, which in this case, holds together other stuff, and bears the traces of its own depositing. In essence, paint becomes goo. The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have yielded numerous experiments in the literalism of painting-works by assorted Action Painters, Actionists, Nouveau Realistes, members of the Gutai Group, and, more recently, a host of artists clumped together under categorical terms like “new abstraction” or “process painting.” Among these, one finds the likes of Pia Fries, Bernard Frize, Katharina Grosse, James Hayward, Jason Martin and Scott Richter. These are artists who are setting aside questions of abstraction or representation in favor of what might better be described as a kind of ordered materiality-the slowed, more methodical descendant, sans the psychological and emotional implications of what broadly was understood as action painting. At the present, Pollock and Rock bookend this epoch in painting. As suggested by the invocation of Sobel, Pollock was not the first to lead down the path to a more literalist approach to painting, but he was arguably the most iconic-effecting and affecting the direction of a particular strain of painting, as well as a way of thinking about art objects, so powerfully as to be, if not the one who started it all, none the less the one, or the poster child of those who brought to bear such concerns amidst the course of modernist painting. Rock--whose dollops of silicon are the puffy descendants of Pollock’s drips and pours of paint, and whose imbedded shells, artificial flowers and other objects are the decorative kin of Pollock’s string and pebbles-no doubt will not be the last in this literalist lineage, in which artist after artist has pushed on until we arrive at work with the sort of steroidal bravura of Rock’s. But Rock is the latest in the line, and his approach to the approach is so aggressive, adaptive and devoted as to make a successor seem distant. In their physicality and implication, Rock's works are nothing like the works or words that came with another branch of literalist practice which, stemming from the non-gestural precision of geometric abstraction, but no-doubt spurred on by a literalist, material-oriented understanding of gestural painting and sculpture, evolved into Minimalism. In works and in words, minimalist artists like Robert Morris and Donald Judd sought to ensure the possibility of art that simply is-outside of categories of painting or sculpture; outside of categories of abstraction or figuration; and free of expression. Such a goal was pursued by fusing a literalist approach to materiality-avoiding any attempt at making a material try to be something else-with a distilled, purist formalism. The product had to eliminate reference and expression (hence the elimination of the record of the artist's working hand) but nonetheless had to maintain evidence of the artist's plan. But while it is true that minimalist works generally are non-figurative and in that way neither representational nor referential, and while it is arguable that they are perhaps even beyond abstraction, they nonetheless deal in a revelation of values, concerns and attitudes. In just being what they are, and in being so within the context of art, they speak, and one might argue that to do so is simply to engage in a different kind of representation and abstraction. Neal Rock's works in many ways have little to do with minimalism (just look at them), but the extreme example of how Minimalist works managed to represent and refer by attitudinal implication even while attempting to simply, literally, be, provides a springboard for understanding the work of Rock. Pollock famously said that the artist of his age would need new means to express the age of the airplane, the atom bomb, and the radio, all of which now seem like both sources and euphemisms for mid-twentieth-century existential wonder and worry-sights and signs of intertwined preoccupations with possibility, presence, transcendence, annihilation and nothingness. Pollock never made pictures of atom bombs or airplanes or radios, and though in his late years he turned his dripping and pouring into a style for rendering figures, and though some have argued that even in his all-over paintings, one finds pictures-vague atmospherics and closeted figuration-it seems that the real draw of works like No. 29, and those made in the couple of years before and after, is their capacity to reveal attitude and concern, and thereby resonate with their viewers, without ever picturing anything. The paintings simply, literally, are what they are, and yet in their ordering of materiality, they speak of the anxious awe of an age for which, in words, atom bombs, airplanes and radios somehow summed it up. It comes as no surprise that Neal Rock's works bear the visual evidence of their descendance from the turn-of-the-fifties work of Pollock, as they take a cue from, and also update, his project-producing a gesturally ordered accumulation of material that pushes beyond abstraction into a literal presence that simply is, but that simultaneously speaks of its age. It comes as no surprise as well that Rock’s work is substantially different from that of Pollock, not just because it arrives at the other end of a long chain of experimentation in painting’s terrain of the literal, but also because his is a different age. Rock has himself spoken of interests in infection, in horror movies, in hidden languages, and in confections, and his work has been discussed significantly in relation to the last of these, but none of these are what he pictures or even abstracts, and none ultimately are what his work is about. Rather his works speak, or perhaps one should better say his works ooze, of a cultural moment of which these things are symptomatic or euphemistic. Is it any wonder that Rock's works invoke a sweetness that cannot be separated from petulance, pestilence and pustulance? Is it so surprising that his infection/confections seem perpetually to spread, enveloping themselves and their environs in a kind of bloated baroque theater? And considering that Pollock needed fluidity in the ordering of his material to express his age, is it any wonder that Rock needs materials that ooze, cake, clump and clot? Is it any wonder that as, in Pollock’s words, "each age find its own technique," Neal Rock, has in this age, found silicon pumped through an icing funnel? Christopher Miles

|