|

|

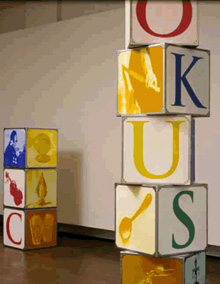

Kimberly Austin "The family is the cradle of the world's misinformation. There must be something in family life that generates factual error. Overcloseness, the noise and heat of being. Perhaps something even deeper, like the need to survive. The family process works toward sealing off the world. Small errors grow heads, fictions proliferate." The specific family described by Don DeLillo in his 1985 novel White Noise is that of the narrator, but it could just as well be the Family of Man. At her death, Kimberly Austin's Aunt Mary left a legacy of religious icons statuettes of Jesus, Mary, and her favorite saints and vintage photographs recording the history of her Catholic family back to Portugal. Many of the photographs show the female members of her family in white dresses, garbed as virgins for sacramental events- baptisms, Holy Communion, confirmation, matrimony. "I was fascinated with these images that revealed femaleness as pure, innocent, beautiful, and untainted. The white costume transformed the women and girls into variations of the Madonna and placed them securely within the boundaries of feminity." As a child, Austin was proud to resemble her mother. She offered consolation when her mother's relationships with men turned sour. She watched her mother phase in and out of believing herself to be ugly and undesirable. She saw her mother's identity shift, chameleon-like, to match the version reflected in the mirror of her current man. Austin developed a pain in her left knee at age 14. She was diagnosed with bone cancer, and the leg was amputated. Chemotherapy trigged the loss of hair and body fat. The heavy prosthesis she was encouraged to adopt frightened her. In the midst of her puberty, having been well tutored by the women in her family about what did and did not constitute ideal womanhood, Austin weighed 65 pounds, was bald, and had only one leg. "I felt sexless and different. Strangers could not decide whether I was a boy or a girl." Thus began Austin's investigation into the icons and issues of sexual identity. For a younger artist, Austin's curriculum vitae is already impressive; it lists six solo exhibitions and more than two dozen group exhibitions. Through subtle deconstruction of the Western cultural archetype of the bride (white-clad, virginal, Madonna-like, submissive), and of the fine arts' classical depiction of the nude (anatomically perfect), her work to date has methodically destabilized those characteristics defined as masculine and feminine. In this latest body of work, Learning Normalcy, Austin takes the issue of gender distinction literally back to the ABCs. Her sized-for-adults replicas of children's building blocks present letters of the alphabet and body image specifics on the same rung of the ladder of awareness. In this work, she says that opinions may form out of the elemental components of the language we share. These essential symbols comprise the gender code of our culture. A is for apple and airplane, arteries and alligator, and adolescence. B is for boy and brush, boat and brain, and breeding. C is for car, corset, compass, clown, and condom. Austin's building blocks refer to the development of personal identity and knowledge of the body. Their textual messages come from home health manuals, children's hygiene instruction, and sex and marriage guides, all dating back to the turn of the century. Their topics relate to what was then regarded as normal, appropriate behavior. "Scandals and sensational episodes of a gross sexual nature sometime have their origins in the irresponsible actions of a nymphomaniac subject." The textual excerpts, such as that above, from the S block, resonate with the authority of absolute knowledge that we, as contemporary readers, recognize as outdated, more moralistic than rational, and in this particular case, perhaps dangerously patriarchal. Austin's work is effective because it instructs not through confrontation, but through subterfuge. Her blocks are inviting playthings, offered to viewers in a spirit of generosity. Surfaced with saturated color and images printed in a soft-focus, nostalgia-triggering format, they were made to be touched, handled, rearranged. If we register shock, however strong or mild, at the juxtaposition of a dildo and a doll, an erection and an emery board, what does that say about the way our brains compartmentalize and assign value to the infinite number of information units we must absorb each minute of a waking day? By offering us the opportunity to witness ourselves as we experience these little shocks, Austin suggests that we, as a culture, might benefit from being weaned away from our inherent reflex to categorize, specifically with regard to gender characteristics. We might ask ourselves, until each individual arrives at her of her own answer, why some images -the submissiveness of women, the aggressiveness of men are still so easy to accept, and others especially those related to bodily and sexual functions - can still produce discomfort or unease. Austin cites Sir Kenneth Clark's The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form on the subject of the idealized male and female forms: "According to Clark's model, the feminine and the masculine are isolated and mutually exclusive. The mind represents the elevated realm of reason and the body resides in the physical domain of earthly pleasures." Even this idea no longer hold in American culture. The relationship of the body to "earthly pleasures" is presently suspect, driven underground by forces emanating from the political left and right, and there is a need for a whole new language of sexuality, gender identity, and body-mind connections. In this context, Austin's deconstructive segue, from issues of gender identity back to the alphabet, seems a good way to begin. Roberta Lord

|